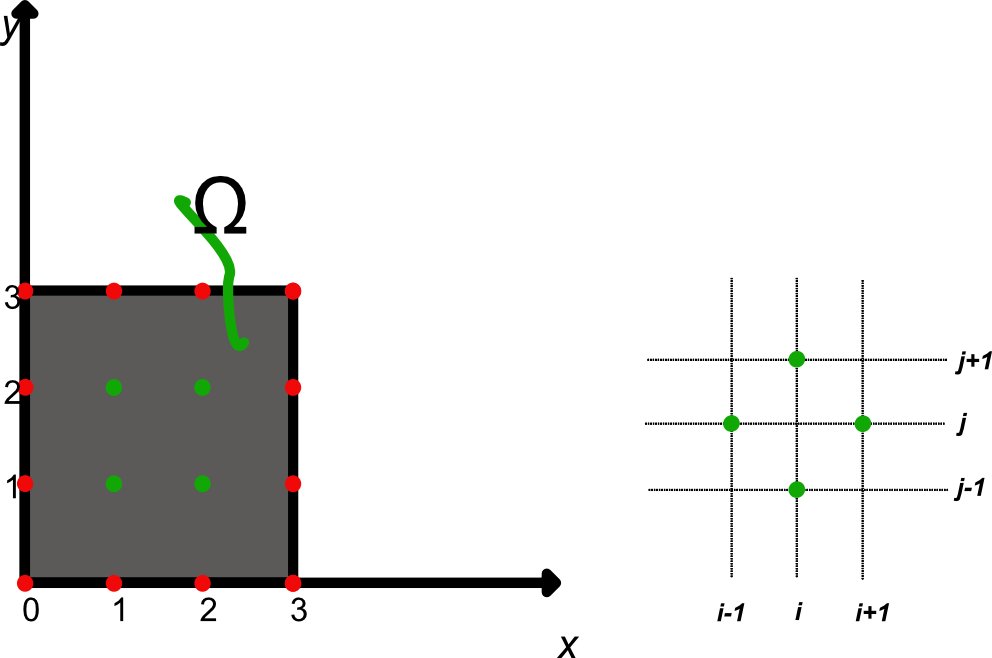

The computatinal molecule; also called stencil, is the key concept to the theory and the implementation of finite difference methods. Finite difference methods seek to find numerical solutions to partial diffferential equations. The computational molecule is a geometric arrangement of a nodal group that relate to the point of interest. For example if we want to calculate the temperature in the middel (green points) of a slab knowing the temperature of the slab on the sides (red points).

Let \(u(x,y)\) be the temperature \(f\) at the point \((x,y)\) and let \(f\) be zero on three sides, that is, \(f(0,0) = f(0,1) = f(0,2) = f(0,3) = f(1,3) = f(2,3) = f(3,3) = f(3,2) = f(3,1) = f(3,0) = 0\) and let, \(f(1,0) = 1\) and \(f(2,0) = 2\). Now we want to estimate the temperature \(u(1,1), u(1,2), u(2,1)\), and \(u(2,2)\)

We can illustrate this by the following simple value problem,

\(\Delta u = 0\) in \(\Omega\) \(u = f\) on \(\partial{\Omega}\)

We can use the finite difference ferences method by replacing the partial derivatives by thier approximating the difference quotiets as follow:

\[\frac{\partial{u{(x,y)}}}{\partial{x}} \approx \frac{u(x+h,y)-u(x,y)}{h}\] \[\frac{\partial^2{u(x,y)}}{\partial{x^2}} \approx \frac{\frac{u(x+h,y)-u(x,y)}{h}\frac{u(x,y)-u(x-h,y)}{h}}{h}\]Taking a single forward difference and the second derivative, we have:

\[\frac{\partial^2{u(x,y)}}{\partial{y^2}} \approx \frac{u(x,y+k) -2u(x,y) + u(x,y-k)}{k^2}\]Setting \(k=h\) and solving the equation, we have:

\[0 = \Delta{u} \approx = u(x+h,y) + u(x-h,y) + u(x,y+k) + u(x,y-k) - 4u(x,y)\]Now the boundray value problem has reduced to a problem in the matrix form:

\(\begin{pmatrix} 4 & -1 & -1 & 0\\ -1 & 4 & 0 & -1 \\ -1 & 0 & 4 & -1 \\ 0 & -1 & -1 & 4 \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} u(1,1) \\ u(1,2) \\ u(2,1) \\ u(2,2) \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} 1 \\ 0 \\ 2 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix}\) which has the solution

\[u(1,1) = \frac{11}{24}, u(1,2) = \frac{4}{24}, u(2,1) = \frac{16}{24}, u(2,2) = \frac{5}{24}\]From the implementation point of view we have,

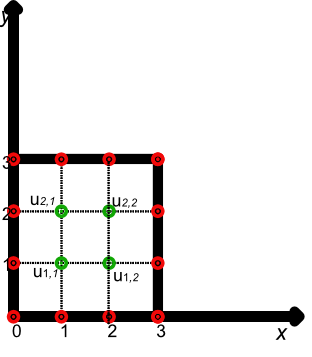

\[\begin{pmatrix} 4 & -1 & -1 & 0\\ -1 & 4 & 0 & -1 \\ -1 & 0 & 4 & -1 \\ 0 & -1 & -1 & 4 \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} u_{1,1} \\ u_{2,1} \\ u_{1,2} \\ u_{2,2} \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} u_{1,0}+u_{0,1} \\ u_{2,0}+u_{3,1} \\ u_{1,3}+u_{0,2} \\ u_{2,3}+u_{3,2} \end{pmatrix}\]here we shifted the notation \(u_{i,j}\) to denote the \(ith\) row and the \(jth\) column of the grid in the following figure

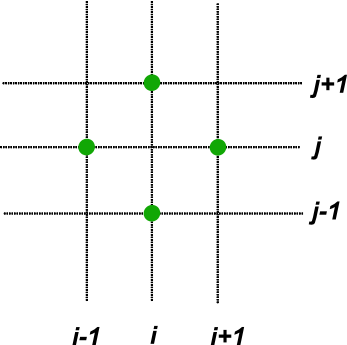

When a numerical scheme is being finalized for implementation capital letters U are often used to denote the discretized solution as contrasted to the use of lower case letters for the analutic solution u. The stencil of this method is the following graph, this is called the five-point stencil for discretizing the Laplacian \(\Delta\). It catalogues which points are used in the scheme.

By including more points in the averaging, one can obtain higher-order approximations to \(u\), but at a higher cost in computing time. Five-point stencils are used for second order elliptic partial differential equations. The accuracy of a scheme, usually given in terms of an error (\(O(h^n)\)) where \(h\) is the grid spacing. This can be determined from a Taylor series expansion.

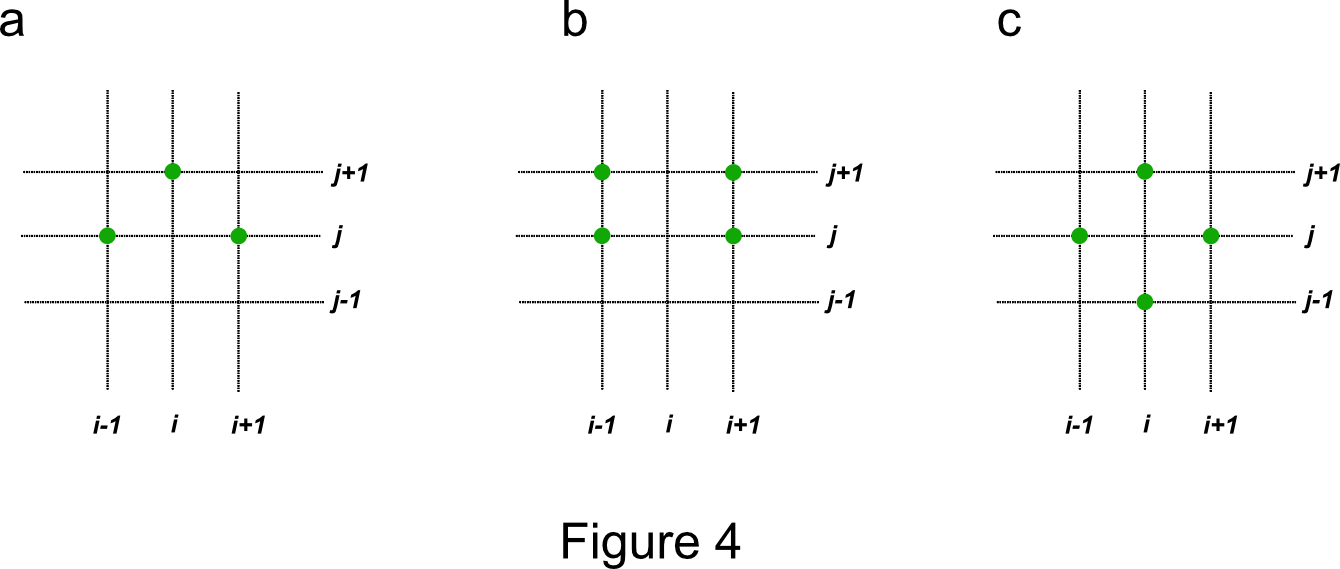

Figure 4 below show three important stencils, two for parabolic equations and one for hyperbolic equations.

Figure 4.a is the stencil for the forward-Euler treatment of the heat equations. The discretized partial differential equation is

\[\frac{U_{i,j+1}-U_{i,j}}{\Delta t} = \frac{U_{i+1,j}-2U_{i,j}+U_{i-1,j}}{(\Delta x)^2}\]from which the algorithm of the scheme is

\[U_{i,j+1} = U_{i,j} + \frac{\Delta t}{(\Delta x)^2}\left[U_{i+1,j}-2U_{i,j}+U_{i-1,j}\right]\]This scheme is said to be explicit because the solution $U$ on the next $j+1$st level may be explicitly calculated from known values of $U$ on the $j$th level. Now writing the algorithm as

\[U_{i,j+1} = (1- 2r)U_{i,j}+r(U_{i+1,j}+U_{i-1,j})\]reveals the important ratio $r=\Delta t/(\Delta x)^2$.

If the ratio $r$ is equal to zero the solution does not advance in time so we can’t take it. However, if the ratio $U_{i,j+1}/U_{i,j}$ exceed 1, the algorithm has a hope of convergence. If we ignore the two-side contributions, the ratio is exactly $(1-2r)^{-1}$. We need to take $r<1/2$ to avoid any divergence. More analysis shows that for

\[0<r\leq 1/2\]the finite difference solution $U_{i,j}$ converges to the solution $u_{i,j}$ of the differential equation as $\Delta t$ and $\Delta x$ go to zero.

** APPENDICE B (Introduction to Partial Differential Equations and Hilbert Space Methods, 3nd Edition. Karl E. Gustafson)